Fool's Gold: How Unrestrained Greed Corrupted a Dream, Shattered Global Markets and Unleashed a Catastrophe: How an Ingenious Tribe of Bankers Rewrote ... Made a Fortune and Survived a Catastrophe by Gillian Tett

Fool's Gold: How Unrestrained Greed Corrupted a Dream, Shattered Global Markets and Unleashed a Catastrophe: How an Ingenious Tribe of Bankers Rewrote ... Made a Fortune and Survived a Catastrophe by Gillian Tett

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I've done a fair amount of reading about the Panic of 2008, and Gillian Tett's "Fools Gold" explains the exotic investment instruments at the heart of the panic better than any other work I've read. A group of derivatives traders at J.P. Morgan created commoditized credit default swaps in the early 1990s as a way to move risk off the company's books, freeing up capital for lending and investment that otherwise would need to be held in reserve. Morgan made payments to AIG, which assumed the risk that Morgan's assets would go into default. Derivatives traders at other firms began assembling securities backed by subprime mortgages, trying to put together instruments that would be just risky enough to obtain returns but safe enough to obtain AAA ratings. They then paid AIG to assume the risk of the mortgages underlying those securities going bad. However, many institutions kept what they thought were the least risky of these mortgages on their own books, as they could not obtain much in the way of returns on the securities that they would back. The whole thing was unregulated by government, and the ratings agencies were easily bamboozled into turning poo into gold (as it turned out). As the cruddy mortgages went bad, AIG began to take on water. When the less risky mortgages went bad, the financial institutions themselves sank.

Interestingly, J.P. Morgan did not get into the business of mortgage backed securities. Morgan's mathematicians could not put together a risk model with the kind of integrity to which they were accustomed. First, they had no data on what could happen if real estate values ever declined. Second, they had no long-term data on default rates for the kinds of subprime mortgages that proliferated in the early and mid 2000s. Moreover, Morgan/Chase chairman Jamie Dimon pushed the concept of a "fortress balance sheet" containing rock-solid assets on which the bank could rely if things went to hell. Dimon pushed Morgan's derivatives traders to investigate getting into the business of mortgage backed securities a couple of times, but, consistent with the notion of a "fortress balance sheet," he accepted the traders' reasons for staying away from that business.

The book contains a brief account of the events leading to the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy that turned a situation into a panic, and concludes with Tett's cultural analysis of U.S. and U.K. investment houses.

View all my reviews >>

Tuesday, September 15, 2009

Fools and Their Money

Sunday, December 07, 2008

Good Books

The TLS books-of-the-year edition is out. Alas, mine usually makes it here a couple of weeks late. I suspect that the print edition will have recommendations from many more reviewers than the online edition offers. I used the best books list to pick up a couple of excellent books last year; perhaps I'll do the same this year.

Or maybe I'll just wait for the next Stephanie Meyer vampire novel to come out. Confession--I've actually not read any of Meyer's books, though DW has, and three of them are in the bookcase on my side of the bed. We saw Twilight and Quantum of Solace on successive days last weekend. Surprisingly, I thought Twilight the better of the two. Love Daniel Craig as James Bond, but, man, Quantum is just plain dull.

Saturday, July 12, 2008

The Magic Bus, Death Edition

Wilderness . . . not only offered an escape from society but also was an ideal stage for the Romantic individual to exercise the cult that he made of his own soul.

--Roderick Nash, Wilderness and the American Mind (quoted by Jon Krakauer)

Christopher McCandless died alone inside an abandoned bus on an Alaskan trail in August 1992, and, if youtube is any indication, the bus has become a shrine--to what, exactly, I don't know. Nothing against McCandless; I've always had a fondness for people who march to the beat of a different drummer, and certainly there are a fair number of people who yearn for what they perceive as a simpler, more primitive life, a life that will provide them with a spiritual epiphany. I say "what they perceive as" based on McCandles's diary entries and what litle I've read about the amount of time and energy hunter/gatherer types spend hunting for game, gathering edible vegetation, warding off disease, and staying warm. Certainly that kind of life is more primitive, but simpler? I'll give my eight hours a day to the U.S. Courts, thank you.

Into the Wild is Jon Krakauer's meticulously researched and brilliantly written account of the last two years of McCandless's life. McCandless graduated from Emory University in 1990, then went on the road. He changed his name to "Alexander Supertramp" and cut off contact with his family. He frequently went days without eating, and lived on rice and whatever he could hunt or gather. Finally, in 1992, he took off for his great Alaskan adventure, a trip he thought would bring about an inner spiritual transformation as he lived off the land. By July 1992, McCandless's diary entries indicated that he was ready to leave the wilderness and return to society. The problem was, McCandless was untrained and unprepared to live in Alaska. The river he had walked across to get to his bus had swollen and become impassible by the time he was ready to leave, and he hadn't bothered to obtain a detailed map that would have directed him to an easy way across the river a few hours from where he was. So he went back to the bus to wait things out. Something went terribly wrong at the end of July--McCandless belived he had eaten toxic potato seeds--and he starved to death by the middle of August. Krakauer opines that a toxic mold or fungus that had grown on the seeds imparied McCandless's ability to metabolize food. Whatever caused him to starve, Christopher McCandless weighed 67 pounds when his corpse was found.

McCandless's death made national news, and Outside magazine assigned Krakauer to write an article. The article led Krakauer to people who had known McCandless in the final two years of his life. His interviews with those people and McCandless's diaries allowed him to piece together a gripping narrative of an adventurous but tortured soul in search of himself. McCandless was obsessed with Tolstoy, Thoreau, and Jack London, and his extensive wilderness adventures somewhat emulated his favorite authors.

McCandless detested his materialistic (by his standards) parents, and he rejected their offers of a new car and a mommy/daddy scholarship to law school (he did what?) Krakauer himself is a wilderness adventurer, having disappointed his own father by rejecting the family's one true path to success, also known as Harvard Medical School. He drew upon his own experience climbing a glacial mountain in Alaska in an attempt to understand McCandless. Krakauer felt vibrant and was intensely focused throughout his climb, as he was in all his adventures. Danger brought him alive. McCandless evidently had the same kind of feelings throughout his adventures. The most obvious difference is that, although Krakauer took huge risks, he was a trained, experienced climber who made appropriate preparations. A less obvious difference is that Krakauer didn't come off as all that interested in using his adventures to gain a complete spiritual transformation.

The most dangerous thing I've ever done in the great outdoors is some mild-mannered open water diving. Diving provided me not with the thrill of danger, but rather a feeling of tranquility, something that was badly needed. I haven't been in a few years, but I'm planning to go down again one of these days. I did go hiking once in the Bear River Range in Utah with no compass and a small supply of water, and I felt terribly stupid when I got lost. However, I was able to see the parking lot from the highest peak and maintain my sense of direction until I got back to the car. One of my fond fantasies is to hike, camp, and run the Rio Grande rapids in the Big Bend region of Texas. If I go, I'll attempt to be properly prepared and provisioned.

Into the Wild brought the movie and novel Fight Club to mind. Chris McCandless and Tyler Durden shared a desire for a return to a primitive lifestyle, and both had inter-generational issues. McCandless tested his body by living in an extreme manner on the edge of society, while Tyler and his followers tested their bodies by having the crap beaten out of themselves. McCandless, however, became an anarchist and withdrew from civilization, while Tyler became a fascist and attempted to create anarchy by destroying civilization. I suppose sons have always had issues with their fathers--Oedipus Rex is rather an old play--and father/son issues have persisted even after Freud has gone out of style.

The book also raised one issue of which I was vaguely aware but had not articulated--the responsibility of an individual to conduct himself or herself in a particular manner to spare the feelings of his or her friends and family members. I have thought some about living my life in comformity with the expectations of others (I agin' it as a general proposition, but I suppose I admire nonconformists far more than I emulate them), but not so much about regulating my actions to spare their feelings. Chris McCandless's relatives wondered aloud how he could bring them so much grief. It's a fair question. However, apart from acting on an actual death wish--something Krakauer didn't see in McCandless--I don't know that one should be responsible for the feelings of anybody beyond his or her spouses and children. Beyond that, one's life is one's own, I suppose.

As for transformative spiritual experiences, I'm dubious about reliance on external stimuli, without something more, though I suppose that some experiences and phenomena are more helpful than others. In the end, however, the actual transformation occurs inside the individual, and can't be borrowed from nature or any person or institution. On second thought, I suppose that intense physical activities requiring complete concentration and perfect coordination of mind and body tend to eradicate the distinction in Western thought between mind and body. Nondualist Eastern thought rejects such a distinction in the first place. Perhaps one can gain a kind of existential, experiential transformative spirituality through adventures like McCandless's.

I can see why people see seomthing admirable in McCandless; I can also see why others see him as a reckless idiot. What I don't get is why people still make pilgrimages to what McCandless called his Magic Bus. Now I've got to see Sean Penn's movie version, which features the bus and other Chris McCandless locales.

Monday, June 23, 2008

Of Families and Frontiers

DW's family reunion last week was a success, as some of the gentle readers of this space can attest. None of the uncomfortable scenarios I feared materialized, and my blood pressure remained normal the entire time. I would like to send all good karma, positive energy, and prayers to the family of one gentle reader whose grandson was struck by a motorcycle shortly after the family returned home.

This was a reunion of DW's parents and siblings and of my FIL and his siblings. My FIL's family on both sides has been in Utah and Idaho since the 1840s. The earliest of those were genuine frontier settlers--ranchers and farmers, mostly--whether they intended to be (in the case of the Mormons) or not (one ancestor's family stopped in Almo, Idaho, on the way to California and just stayed there). Some of DW's relatives currently work the land, and my FIL is an agricultural economist, but DW and her siblings grew up in urbanized settings, with only occasional exposure to the arduous physical labor of ranchwork. When I was a kid in Oklahoma, our yard bordered on a cattle farm, but I knew absolutely nothing about the work that went on back there. Neither of my parents and none of my grandparents were involved with agriculture of livestock, so I have less of a connection to the land than does my DW.

The mythology of the Old West and the westward-shifting American frontier, of course, have always served as part and parcel of the definition of who and what white Americans are, realizing, of course, the violence and injustice in taking much of that frontier from its native inhabitants. Also, the ideal of the American small farmer has been a part of our politics since Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton disputed the nature of our country. The taciturn dirt farmers; the cattle ranchers; the oilmen; the gunsligners; the pious Mormons; the prospectors; the dreamers; the hustling preachers; the evil railroad and mining companies--these all form a part of our collective national self-image, I think, though clearly not part of the reality in the lives of most Americans of my generation. We are reminded of that past by the mythology of the West and by artifacts like the accordion that DW's grandfather took on the trail to pass the time while he tended sheep.

During the reunion of this family with its own roots in what was once a frontier region, and in the days subsequent to that reunion, I just happened to read two fabulous books that address boundaries and frontiers, albeit in very different ways. I liked Cormac McCarthy's The Road so much that I purchased his Border Trilogy, and I finished reading All The Pretty Horses (1992)yesterday. The plot has teenage ranching Texans running away into Mexico, then returning home, in the 1940s. In the Texas these boys knew, property transfers (in this case, horses) were effected with contracts and lawsuits, while in the Mexico they came to know, such transfers were effected with arms and official corruption. The northern Mexico of McCarthy's story somewhat resembles HBO's Deadwood, an outlaw encampment where might made right and life was cheap. All The Pretty Horses ends with our protagonist riding off into the sunset, into an uncertain future in a disappearing frontier.

At the Salt Lake airport, I spotted a copy of Jon Krakauer's Into Thin Air (1997), a firsthand account of the May 1996 Mount Everest disaster. Ironically, perhaps, I began reading the book over the Wasatch Range and the High Uintahs--tall mountains, for sure--and got through about half of it while flying at an altitude only slightly higher than the summit of Everest. Krakauer--an adventure sports journalist--was a member of one of the ill-fated expeditions that climbed to the highest point on the planet on May 10, 1996. As a hypoxic Krakauer descended, an unexpected storm blew in from the South, stranding several climbers at altitudes where human beings are not naturally equipped to be. Krakauer and his fellow climbers found themselves at the frontier of human survival; there were nine deaths, including the leaders of both expeditions. The clouds, viewed from above, appeared innocent enough, but they brought a thunderstorm/blizzard with hurricane-force winds. A series of bad decisions delayed for several hours the final ascent of the two expedition parties at the center of the story, most notably the failure of the leaders of those parties to ensure that ropes were set up at a potential bottleneck very near the summit. The leaders also failed to set a firm turnaround time to ensure that climbers would not run out of supplemental oxygen, whether or not they reached the summit. However, a few climbers assumed a reasonable turnaround time, turned around short of the summit, and survived. The highest peak I've ever hiked is 10,000 feet, and, after reading this book, that may be the highest this lowlander ever hikes.

Monday, June 09, 2008

Fathers and Sons, Postapocalyptic Version

On the recomendation of gentle reader Craig, I read Cormac McCarthy's dystopian father/son novel The Road. Civilization as we know it was destroyed by nuclear warfare several years before the story takes place, and few survivors remain. Among the survivors are a father and son who are constantly on the move, seeking warmth, food, and survival. The unnamed father in the story is a jack of all trades, a la McGuyver, who can make use of anything he can scrounge. He protects his son against cold, illness, predatory gangs of survivors, and a dangerous desire to share the duo's limited resources with other desperate survivors. The son is the father's sole reason for living, and the father is the only other person in the son's life.

The son was born shortly after the nuclear winter began, and, therefore, knows nothing of the world as we know it apart from what his father has told him about it. The son also relies on his father for explanations about the harsh ethics created by their dire circumstances. I kind of related to this aspect of the story, especially when the son would say "it's okay" whenever the father would provide explanations. My oldest son frequently says, "it's okay," as he works to calm himself following a disappointment such as me not taking him on an airplane whenever we drive past the airport (not always successfully, as he destroyed the armrest in my car the other day). Much like the father in the story, I worry about my childrens' futures after my own death. They are entirely dependent on the adults in their lives in order to function in the world, and, barring a cure or a miracle, they will always be largely dependent on other people. They are particularly close to me and always have been. I'm sure they'll fare well without me being around, but the concern will always be there.

Additionally, some poignant moments in The Road involved the father either watching the son sleep or putting him to sleep. Our boys are ages 9 and 11, and we have the same bedtime rituals we had when they were infants. Those rituals have always been almost sacred to me.

ETA: I recommend this book to any gentle readers who might be expectant fathers. You know who you are.

T uses anything that looks like luggage to feed his fantasy of driving to the airport and boarding an airplane. He mostly used plastic first aid kit boxes, but brought out my old briefcase once or twice. He's happy as a clam riding around town with those containers in the car, at least until we drive past the airport.

Monday, February 25, 2008

Language Cake

I started reading Irish novelist Joseph O'Connor's Redemption Falls the other day. The book is set in the immediate aftermath of the American Civil War; perhaps it's a kind of new wave Gone With the Wind (which I found rather dull, quite honestly). This book was highly praised by critics of all stripes in the TLS, and I can see why. O'Connor's language is like a very rich piece of chocolate mousse cake that I can only eat a little bite of at a time. I find myself rereading paragraphs just for the pleasure of nibbling at the author's delicious dessert of words, so I haven't reached page 30 yet. To wit:

She had not been walking long when it started to happen. Everything was coming to merit attention. A rice-field. Two flies. A dead chicken-hawk in a gully. The eyes of hungry alligators resentful in the slime. All of it seemed equal, which is one definition of madness. The weight of the world had lost proportion.

There were days when she hobbled until the world began to shimmer. The sky billowed around her like the folds of the apocalypse and the white-hot egg of pain in her breast threatened to crack with a seepage of venom.

Goodness knows how long it's going to take for me to reach the end of this novel

Sunday, December 30, 2007

Do not go gentle into that good night, unless you donate your body to science

One of my brothers-in-law gave me Mary Roach's splendid

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers, which I finished reading tonight. Cadavers are used in valuable medical, automotive, and criminal justice research, and organ donors ("beating-heart cadavers") actually save lives. Roach interviewed some of the folks who do this research; indeed, she watched some of it underway. She also discusses some of the unsavory history of cadaver research, and takes a detour through the grotesque topic of medicinal cannibalism. This could have been a dry, technical book, but Mary Roach has a wonderful sense for humor, which shows through on almost every page. On a few occasions, she appears over-eager to see certain events first-hand, grossing out even the professionals in cadaver research. Still, she is respectful of the human beings whose cadavers are being researched and of most of the people whose work she observed first-hand. This is a book that's well worth reading, though you might not want to be seen reading it in a restaurant, as I was earlier today.

Monday, May 28, 2007

Honest Abe, Politician

Doris Kearns Goodwin's "Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln," is difficult to review in a brief blog. Goodwin discusses Lincoln's political skills by way of parallel biographies with his three major rivals for the 1860 Republican Presidential nomination, William Henry Seward, Salmon P. Chase, and Edward Bates. Along the way, Goodwin also discusses the lives of Mary Todd Lincoln, Edwin M. Stanton, Gideon Welles, the Blair family, and other figures in the Lincoln Administration.

Lincoln was the least likely of the four major contenders for the 1860 nomination. He had served on term in Congress, in the late 1840s, and he had lost Senate elections in 1856 and 1858 (back when Legislatures elected Senators). Moreover, he lacked the formal education and media stature that his opponents had attained. Seward was the front-runner by far, but Lincoln emerged as the consensus choice of delegates who were concerned that Seward, whose rhetoric on slavery was more inflammatory than Lincoln's, might damage the Republican Party in their own states.

Lincoln was able to emerge as the consensus candidate thanks to a number of factors, one of which was his cadre of loyal and canny political operatives in Illinois. Lincoln had the rare gift of making loyal allies as he lost elections, and he was a tireless political organizer. His allies were able to obtain the 1860 convention for Chicago before Lincoln made clear that he was a candidate, and they worked the delegates and packed the building with Lincoln supporters. Seward, Chase, and Bates, on the other hand, had the misfortune of alienating important groups and individuals as they won elections; those groups for the most part ended up in the Lincoln camp.

Once elected, Lincoln watched helplessly as the Southern states began to secede and President James Buchanan did absolutely nothing to stop them. Lincoln included Seward (Sec. of State), Chase (Sec. of the Treasury) and Bates (Atty. Gen.) in his cabinet, despite the fact that they had run against him. He later brought in Stanton (Sec. of War), who had personally humiliated him wrt a court case years earlier. This, in a time when one-term presidencies were the rule and not the exception. Seward and Bates recognized Lincoln's greatness, but Chase intrigued against Lincoln in hopes of securing the 1864 nomination for himself. Lincoln held his cabinet of former Whigs and former Democrats together through a mixture of timing, manipulation, and personal humor and kindness. He even kept Chase around, due to Chase's uncanny ability to raise money to fund the Union war effort. It didn't bother Lincoln that Chase was always scheming against him. After he accepted Chase's resignation, Lincoln nominated Chase as Chief Justice, knowing that Chase was absolutely committed to the rights of African-Americans, which Lincoln saw as the most important legal issue that would arise after the Civil War ended. Oh, yeah, and Lincoln held the Union together in the face of a string of military defeats, incompetent commanders, and political defeatists.

Goodwin explores the evolution of Lincoln's views on slavery and race, though that issue is addressed in more detail in Garry Wills's "Lincoln at Gettysburg," another book I highly recommend. Wills discusses the Gettysburg Address in great detail as well, finding influences going all the way back to Pericles. Goodwin, however, does provide an interesting take on the Gettysburg Address. She discusses Lincoln's childhood, in which he listened to his father tell stories ad nauseum. Lincoln himself loved to tell stories, and used stories to drive home important points he wanted to make. In the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln, in a little over two minutes, told the story of the past, present, and future of America:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation, so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Liberty, equality, and democracy are the political ideals of most Americans, whether we may disagree on the precise meanings of those words and whether we have a ways to go before we fully achieve them. "Team of Rivals" is an excellent book, though it is very long and portions of it did not seem particularly relevant, particularly the parts involving minor players like Katie Chase and the various members of the Blair family. I got bogged down in some of that minutiae. However, I like the idea of using comparative biography to show just how exceptional our 16th President really was.

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

Fictional character

There is a statue of fictional character Ignatius J. Reilly outside the hotel that was once the D.H. Holmes department store. "A Confederacy of Dunces" opens underneath the old clock outside of that store. The statue is pretty much hidden underneath an awning, and the front entrance to the hotel is on the other side to boot. Still, Ignatius stands as a monument to this city's literary history.

There is a statue of fictional character Ignatius J. Reilly outside the hotel that was once the D.H. Holmes department store. "A Confederacy of Dunces" opens underneath the old clock outside of that store. The statue is pretty much hidden underneath an awning, and the front entrance to the hotel is on the other side to boot. Still, Ignatius stands as a monument to this city's literary history.

Sunday, September 03, 2006

Egads, he's reading poetry now

Yesterday, I picked up a book of Dylan Thomas's poetry. I only started to appreciate poetry a few years ago; kind of strange, given that I have always worked with the written word. I suppose that the search for meaning leads us naturally into some degree of appreciation for the arts. Anyhow, here's a classic that happens to be one of my favorite poems:

Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on that sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Dylan Thomas

Sunday, June 04, 2006

Local history

I picked up "The Great Deluge" yesterday, a history of Hurricane Katrina authored by Tulane history professor Douglas Brinkley. I'm about halfway through the book now. Brinkley is a dispassionate academic by trade; this book is scathing and judgmental, and, in some cases, rightfully so. New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin is particularly lambasted for his lame leadership during the storm and its aftermath. I gather that Nagin did not provide Brinkley with an interview, but I notice that several individuals who remain in the mayor's inner circle did contribute to the book. The NOPD, FEMA director Mike Brown, Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff, and President Bush also get a big thumbs down from Brinkley. Brinkley is slightly more favorable to Louisiana Governor Kathleen Blanco, though it's clear that she was in over her head. On the other hand, the U.S. Coast Guard, the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, the mayors and police forces of coastal Mississippi, various hosptial staffs, and a good many private citizens are shown to be genuine heroes.

Unfortunately, the book is chock full of typographical errors and misspellings, inconsistencies, and mistakes in geographical references. For instance, Brinkley refers to the residents of St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, alternatively as "Chalemetteans" and "Chalmations," (which some people in Chalmette find insulting), and the Lake Borgne Surge pummelled St. Bernard Parish, not coastal Mississippi. I suppose the book was rushed into print. It is compelling reading, however.

Friday, June 02, 2006

poetry moment

regardless

the nights you fight best

are

when all the weapons are pointed

at you,

when all the voices

hurl their insults

while the dream is being

strangled.

the nights you fight best

are

when reason gets

kicked in the

gut,

when the chariots of

gloom

encircle

you.

the nights you fight best

are

when the laughter of fools

fills the

air,

when the kiss of death is

mistaken for

love.

the nights you fight best

are

when the game is

fixed,

when the crowd screams

for your

blood.

the nights you fight best

are

on a night like

this

as you chase a thousand

dark rats from

your brain,

as you rise up against the

impossible,

as you become a brother

to the tender sister

of joy and

move on

regardless

--Charles Bukowski

Saturday, April 01, 2006

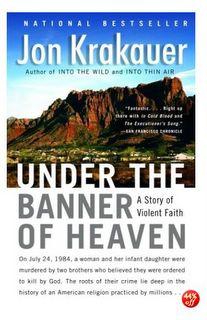

Under the Banner of Heaven

Which comes first? The chicken or the egg? More to the point in Jon Krakeauer's "Under the Banner of Heaven," does harsh, fundamentalist religion create sociopathic killers or conditions in which they may arise, or do sociopaths merely use bits and pieces of doctrine and scripture to justify their criminal behaviors? Krakauer's book appears to move in the first direction, then seemingly makes a turn in the other direction just at the very end.

Krakauer tells the sordid tale of Ron and Dan Lafferty of Utah Valley, who murdered their sister-in-law and infant niece because Ron had received a revelation telling to commit the murders. The Laffertys were self-styled "funadamenatlist Mormons" (FunMos, thanks Todd!) who believed in polygamy and that the main LDS Church marched into damnation when it discontinued the practice of "the Principle." The Laffertys also fancied themselves--or at least Ron--as prophets ("The One Mighty and Strong" foretold in the "Doctrine and Covenants," a holy book of all Mormon-oriented groups).

They also became obsessive about the doctrine of Blood Atonement, which was preached by Brigham Young. Brigham's record regarding that doctrine was tainted by the 1857 Mountain Meadows Massacre, an incident for which the LDS Church disclaims responsibility, but about which the critics of the Church will not shut up. Recent publications make Brigham appear quite complicit, though most of the evidence is circumstantial. The massacre is recounted in great detail, and blame is placed squarely on Brigham. The MMM is a sort of smoking gun for Krakauer's thesis that extreme faith may lead people to extreme acts of violence. It could be, however, that the massacre is more in line with the notion that people are smart but groups of people are mean and stupid, or however that goes, especially when they are led by individual zealots. By the way, the LDS Church recently officially renounced Blood Atonement as a doctrine in order for the Utah Legislature to abolish the firing squad.

Krakauer's narrative consists of alternating chapters about the Laffertys and about the history of Mormon and FunMo polygamy. Some FunMo groups still talk about Blood Atonement, and all adherents of the religions that call themselves Mormon believe in prophets--though, obviously, the institutional churches can have only one active prophet at a time, or they would disintegrate into tiny groups, each following its own guru. Ron Lafferty, who evidently was not a member of ANY of the generally recognized Mormon churches (though he had been excommunicated from the LDS Church) received a hit list in the form of a revelation. Coincidentally, the people named on the divine hit list just happened to be the people Ron blamed for the collapse of his marriage and for his excommunication. That little coincidence suggests to me that Lafferty was simply a sociopathic nut who would have latched onto some oddball interpretation of the doctrines of, say, the Southern Baptist Convention, were he raised in a Southern Baptist environment, in order to justify his murders.

Krakauer's argument gets a little wobbly here, and, to his credit, he also discusses Ron's retrial, at which the defense argued that Ron's religious beliefs rendered him insane. Various mental health professionals--some Mormon, some not--testified convincingly that intelligent, rational people can hold beliefs that are non-rational, or even extreme, without being clinically insane.

Krakauer closes the paperback edition of his book with the entirety of the official LDS Church response to his book (guess what? They didn't like it.) He replies to the response, which mostly critique nitpicky little details and Krakauer's interpretive spin on facts that aren't really disputed. Krakauer, who is not LDS, closes with a plea for a more open examination of LDS history.

Bet he watches "Big Love."

Saturday, February 25, 2006

It's all about farming

I am finishing up my reading of "Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies" (1997), by UCLA Professor Jared Diamond. This is a brilliant book, and one I recommend to anybody interested in understanding why socities developed differently, and at different paces, in different parts of the world. Diamond takes a very broad view of his subject, and his thesis is that the development of food production is ultimately the reason why Eurasian socieites developed the technologies, centralized governments, writing systems, and, as an unfortunate byproduct, the germs and epidemic diseases that allowed them to conquer and dominate the socieites of the Americas, Africa, Australia, and Oceania. The Eurasian development of food production, in turn, is based on the availability of wild crops and wild large mammals suitable for domestication. Early developments in Eurasia (largely the "Fertile Crescent," but also in China) were spread easily throughout Eurasia due to that land mass's East-West access, which allowed societies from Europe to India to China to adopt plant/animal "packages" at similar lattitudes (though, due to geography, the interactions between China and the Fertile Crescent area were much more limited than the interactions between the Fertile Crescent, India, and Europe. Also, the more evenly distributed populations of the Eurasian land mass helped in the diffusion of crops, animals, and ideas, while the more isoloated populations of the other areas of the world were less able to share with each other.

Diamond is very convincing, and he discredits the old, at least implicitly racist, Euro-centric theories that attempted to explain why some cultures progressed more rapidy than others. In his broad sweep and fresh approach to the subject of world history, Diamond reminds me somewhat of the French "Annalistes" of the 1930s, who focused more on issues like the history of climate than on the more traditional subjects of their field. Also, sweeping theories of comparative history have been out of favor for years, and Diamond's book suggests the difficulties inherent in formulating such a sweeping theory; his theory takes into account plant and animal physiology (he is a physiologist by training), epidemiology, economics, political science, sociology, geography, demographics, technological innovation, linguistics, and cultural anthropology--and history too. With knowledge as specialized as it has become, the possibility of forumlating a single, broad theory of the history of the development of human socieites has been greatly reduced from the days of intellectual generalists. There are a few underdeveloped areas in the book, and Diamond himself mentions a few in his 2003 afterword--the role of cultural idiosyncracies, and the assertive proselytizing of Islam and Christianity being a couple of them. I thought he gave the role of religion in social development short shrift, limiting his discussion of religion to its role in supporting the social order in highly stratified societies. Certainly all of what we would call major religions (all of which are relatively recent in the long history of human life on Earth) have served that purpose, but it seems to me that the teachings of different religions have different and powerful influcences on their respective adherents and societies--whatever their unique historical and spiritual claims. Whether you accept Diamond's hypothesis or not, "Guns, Germs, and Steel" is a brilliant, fresh approach to history, and one that makes for a damn interesting read.